Source code: schooling-under-predation.

Introduction

In the natural world, animals exhibit collective behaviors by traveling in groups in a coordinated manner. This phenomenon occurs at both microscopic scales (bacteria) and macroscopic scales (vertebrates). It is called schooling in the case of fish, flocking in the case of birds, and herding in the case of grazing mammals. Schooling helps fish to defend against predators and enhance foraging success. In this project, we chose to simulate the behaviors of a school of mackerels under the predation of a shark.

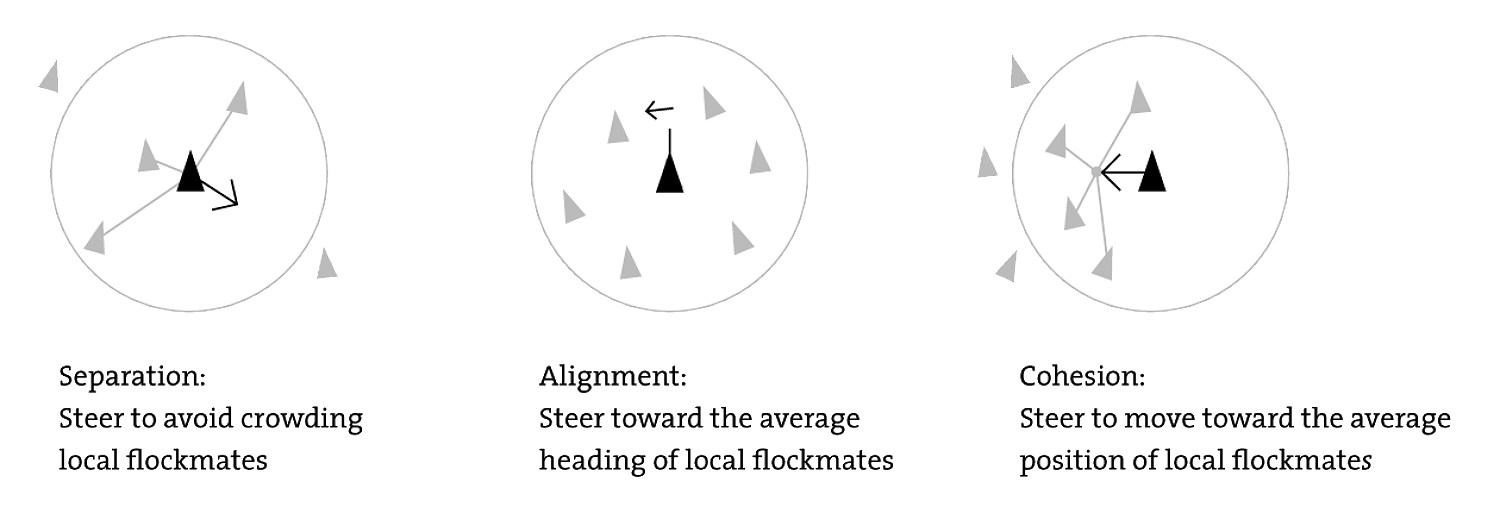

In the infamous work Flocks, Herds, and Schools: A Distributed Behavioral Model, Craig W. Reynolds explores flock movement as the aggregate result of the actions of individual animals, each acting exclusively based on the basis of its own local perception of the world. This is known as emergent behavior. Reynolds developed a computational model of bird flocks and fish schools. In this model, agents (boids) form groups even though they do not have a group identity or even a concept of what a group is. The basic flocking model comprises three steering behaviors:

We took inspiration from these Reynolds rules to implement the schooling behaviors of mackerels. However, our schooling behaviors cannot be directly implemented following the exact algorithm of Reynolds' boids, given the constraints imposed by local sensing and reactive behaviors. Generating the schooling behaviors without requiring the agent's understanding of a global state of the scene is the main challenge that adds value to our project.

Robotic simulation setup

V-REP simulator

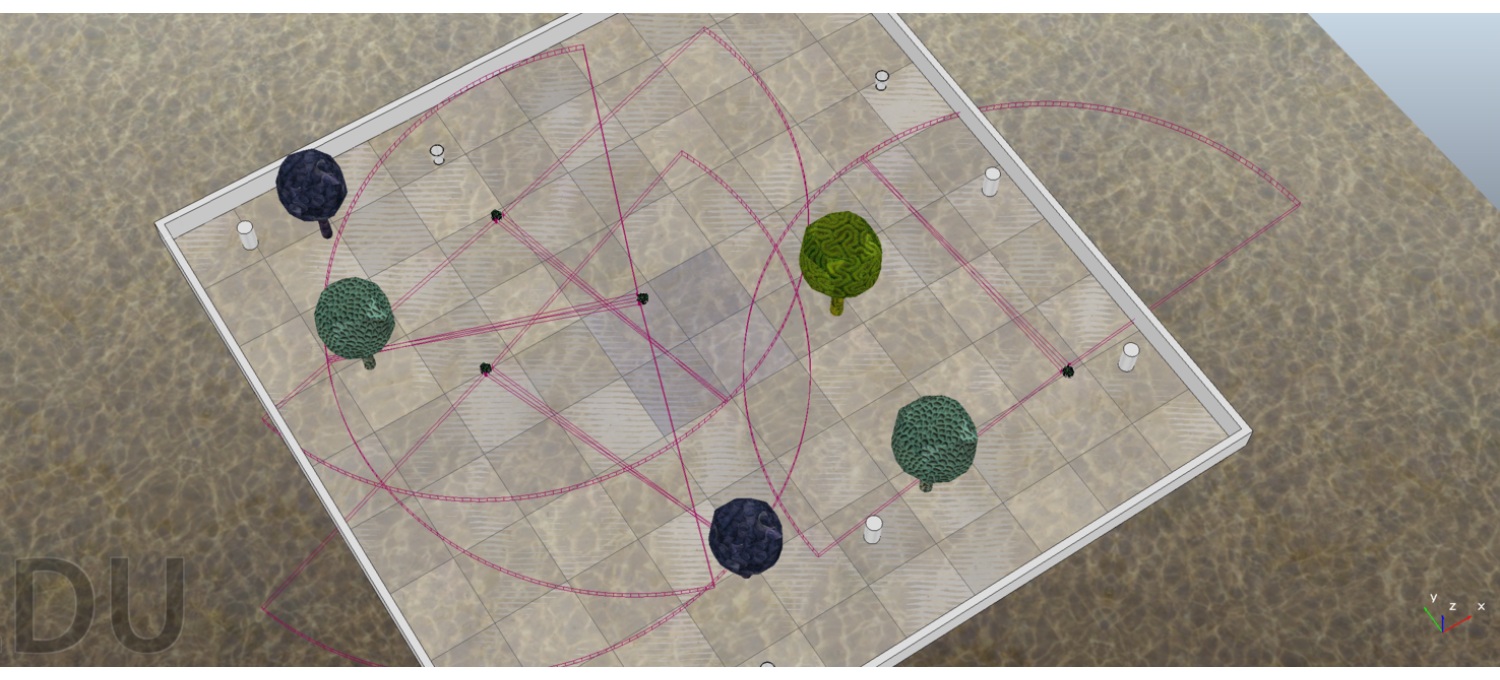

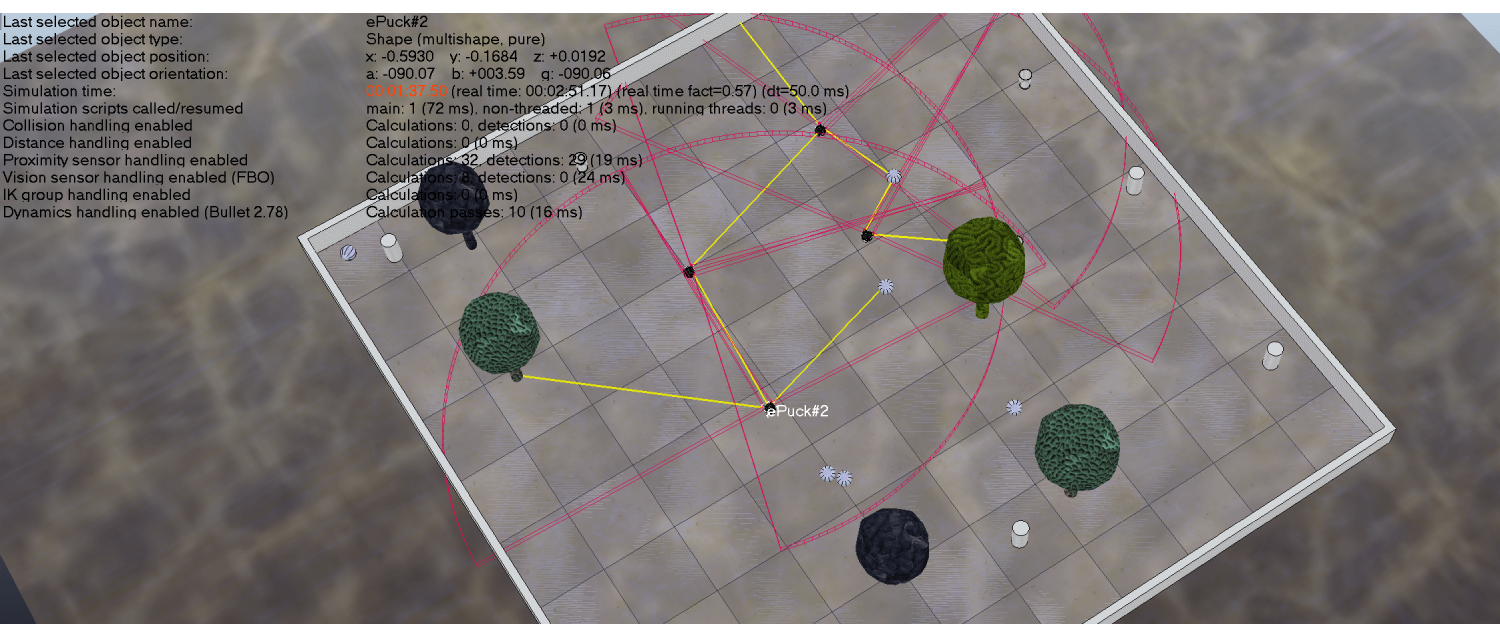

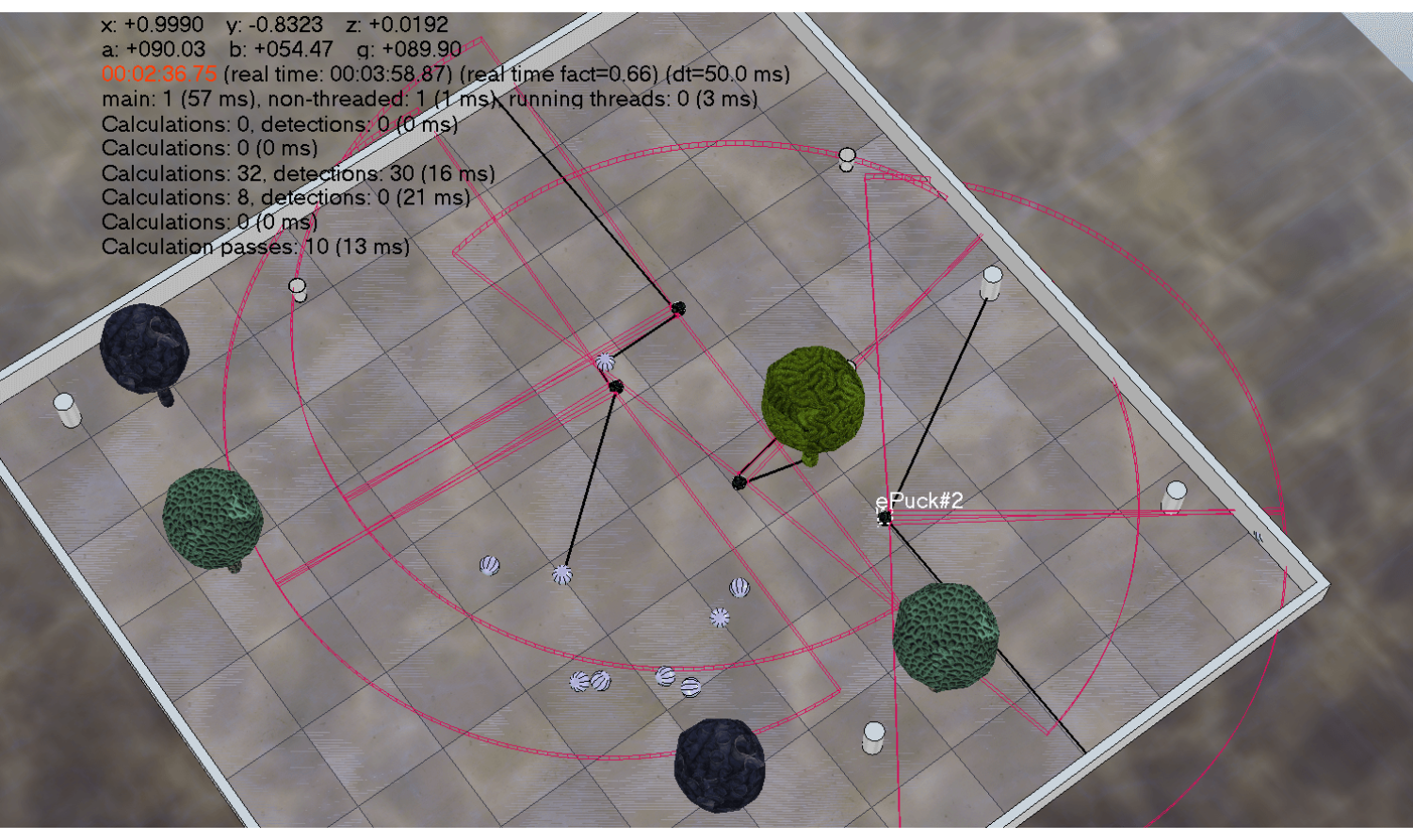

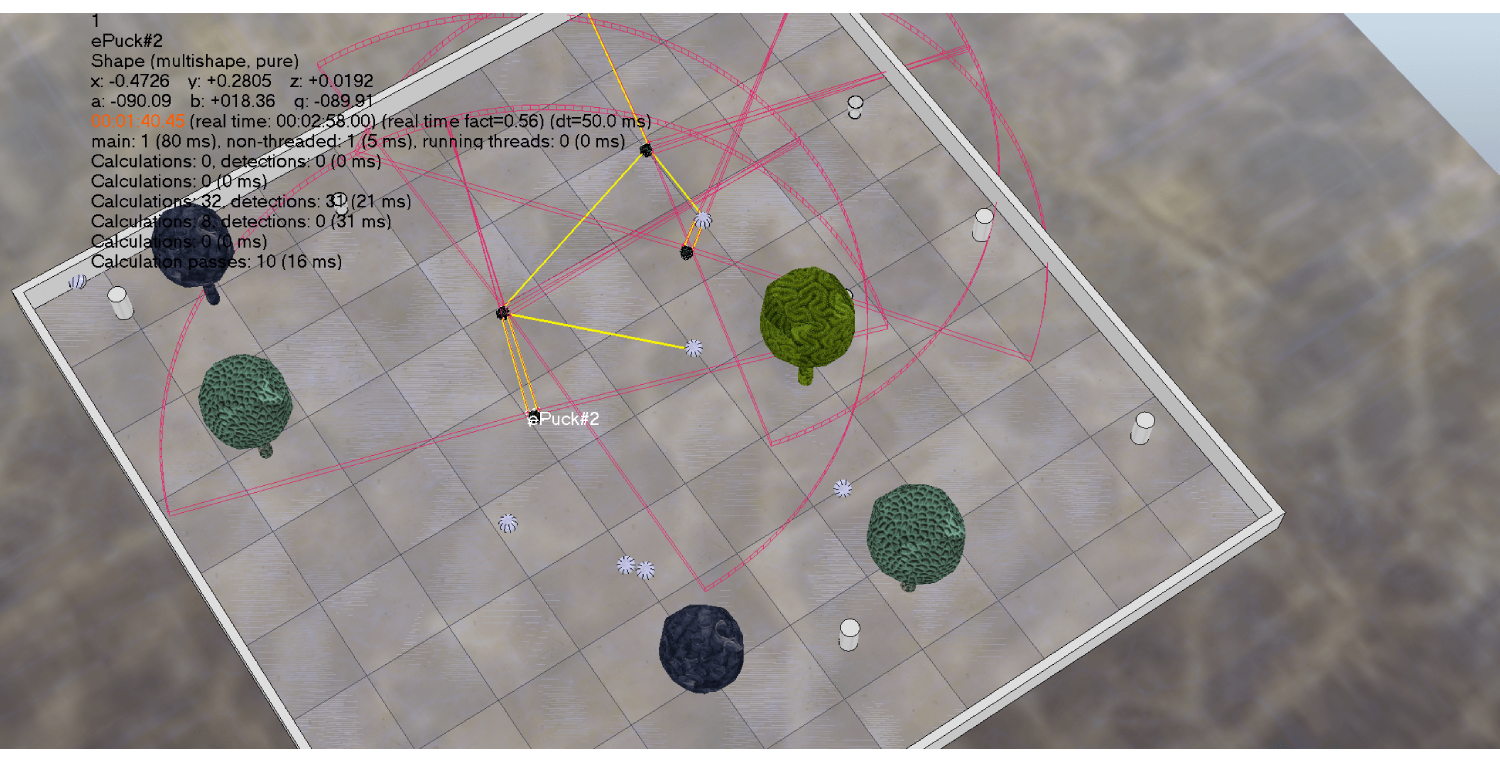

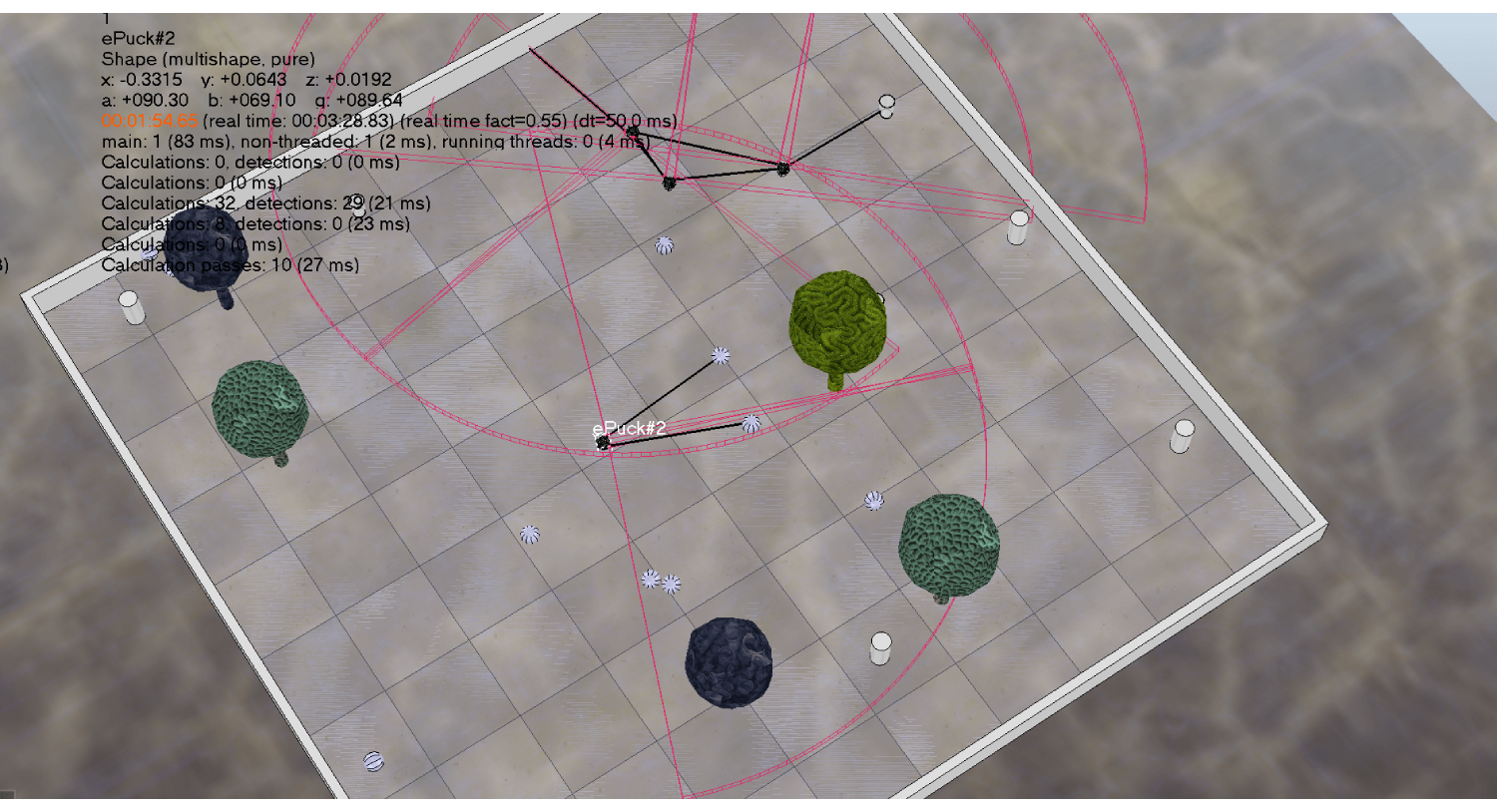

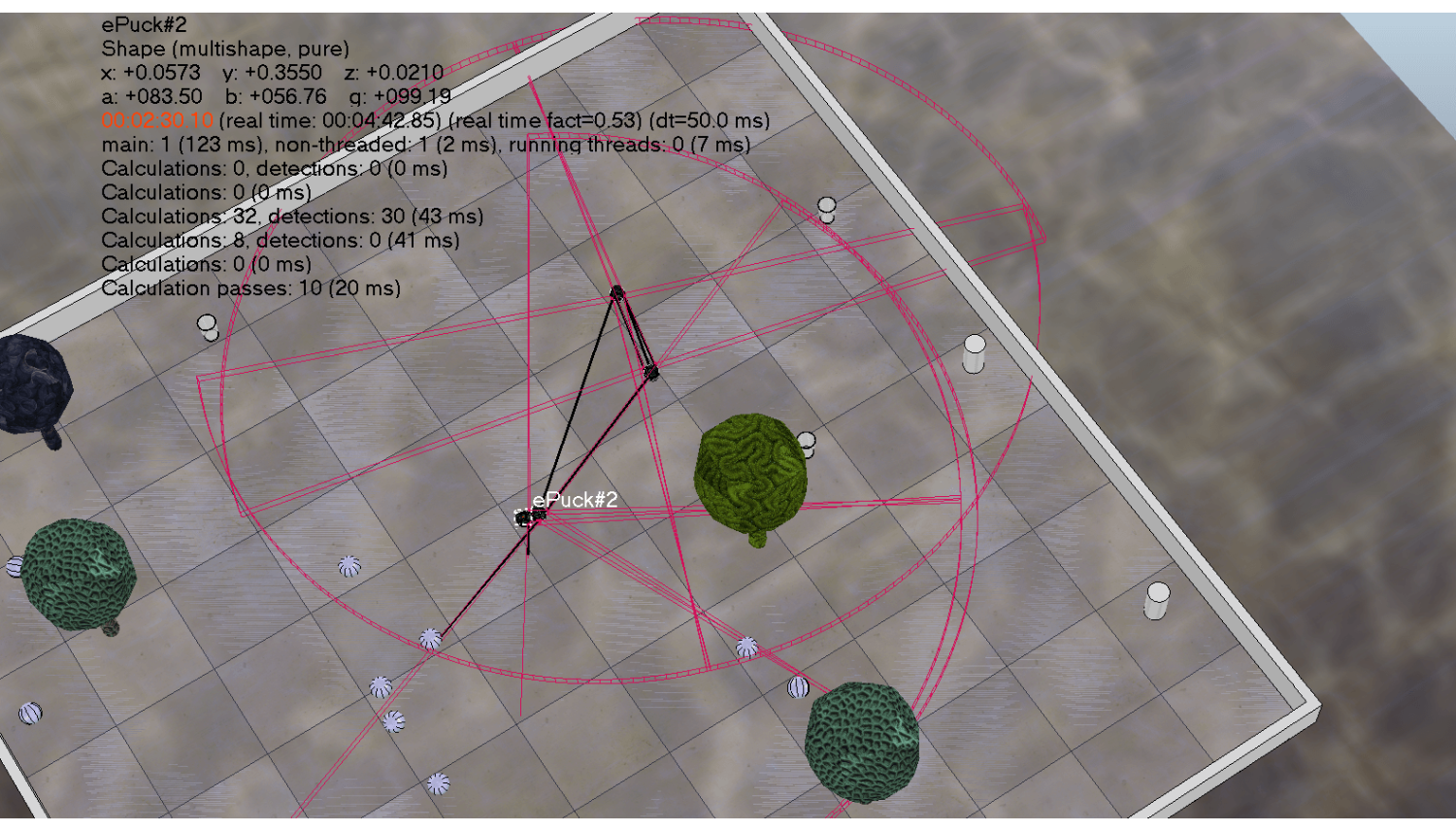

The V-REP (CoppeliaSim) scene has been adapted to the underwater environment through different blue tones and textures. The water texture was provided by CoppeliaSim, whereas the textures of the "corals" were dragged onto the surface of the existing tree objects. The "corals" and the "cups" were placed in this way in order to provide a free area and also to provide collision objects that the robots have to avoid. Our V-REP scene has 3 e-puck mobile robots on the top-left corner as 3 mackerels and the shark locates on the bottom-right corner.

Python controller

The connection between the Python controller manipulating e-puck robots and the V-REP simulator was made using the pyvrep-epuck interface. Instructions to install and set up the sessions can be found in the README.md file of the repository.

Behavioral weighting mechanism

While there are multiple behaviors running in parallel on the same robot, it's necessary to specify the weight of each behavior i.e. how much it will count in the averaging. This weighting can activate a behavior according to some internal drives of the robot i.e. the animal will choose to satiate the need with higher intensity. For instance, a mackerel might split apart from the shoal mates if it's terribly hungry; but if it's just slightly hungry, it will prioritize staying within the group. The animal then evaluates the importance of needs based on a ranking system to represent the trade-offs when there are multiple needs with equal intensities: if the needs for collaboration and food are equivalent, the need with a higher importance level should be satisfied first. The relationship between behavioral weighting, the intensity and the relative importance of needs can be simplified as this equation:

Weight of behavior = Intensity of need - Importance ranking discount

Internal needs

The basic needs of both mackerels and sharks can be defined as below:

# the need to stay close to shoal mates - regulate schooling behaviors

prey.collaboration_need = 0.5

# cohesion threshold - a proximity value smaller than this means the shoal mate is too far away

th_c_min = 0.4

# separation threshold - a proximity value bigger than this means the shoal mate is too close

th_c_max = 0.6

# the need to run away from predator - regulate escaping behaviors

prey.security_need = 0.5

# low energy level increases the need to catch food - regulate foraging behaviors

predator.energy_level = 0.5

prey.energy_level = 0.5

# predator has higher metabolic rate

predator.energy_increase = 0.2

predator.energy_decay = 0.02

prey.energy_increase = 0.1

prey.energy_decay = 0.01

Ranking system of needs

The animal evaluates the importance of a certain need based on an internal ranking system. Internal needs with lower importance level would only be considered if those with higher importance level are fulfilled. In the context of this project, we prioritize schooling over foraging and anti-predation over schooling. In reality, it could be different.

We use discount values to indicate importance level which will be subtracted from the intensity of need. The higher the importance, the lower the deduction value.

# first priority

prey.security_discount = 0.01

# second priority

prey.collaboration_discount = 0.02

# third priority

prey.foraging_discount = 0.03

Routines to track internal drives

These routines - which we call drives - helps the robot keep track of its internal needs and calculate the intensity of them. We adjust the intensity of need based on the fluctuations of threat intensity caused by external stimuli. In some cases, the animal will act in order to keep this value as low as possible. In other cases, the animal will try to keep this value within a desired, predefined range.

The schooling drive: affected by the presence of shoal mates and adjusting collaboration need.

# ensure distance to shoal mates to be within a range between cohesion and separation thresholds

if left <= th_c_min: # the shoal mate is too far away

robot.collaboration_need += abs(robot.collaboration_need - left) # increase the need

if right <= th_c_min: # the shoal mate is too far away

robot.collaboration_need += abs(robot.collaboration_need - right) # increase the need

if left >= th_c_max: # the shoal mate is too close

robot.collaboration_need -= abs(robot.collaboration_need - left) # decrease the need

if right >= th_c_max: # the shoal mate is too close

robot.collaboration_need -= abs(robot.collaboration_need - right) # decrease the need

robot.collaboration_need = min(1., max(robot.collaboration_need, 0.))

The security drive: affected by the presence of the predator and adjusting security need.

# ensure the predator to be as far as possible

robot.security_need = left + right

robot.security_need = min(1., max(robot.security_need, 0.))

The foraging drive: affected by food consumption and adjusting energy level.

if robot.has_eaten(): # ensure the energy level to be as high as possible

robot.energy_level += robot.energy_increase

else:

robot.energy_level -= robot.energy_decay

robot.energy_level = min(1., max(robot.energy_level, 0.))

Implementation of behaviors

Reynold's schooling behaviors

The separation behavior: the desire of a mackerel to steer away from an approaching schoal mate. In Reynolds' work, static collision avoidance and dynamic velocity matching are corresponding to each other and form this behavior. Static collision avoidance depends on the relative position of the shoal mates and disregards their velocities. The coordinating velocity of the animal is based only on velocity and ignores position. Static collision avoidance serves to build up the minimum required separation distance, while velocity coordination generally tends to maintain it. In our case, we developed this behavior based on the basic fear Braitenbergs behavior. The distances to shoal mates are proximity values detected by the two proximity sensors of the robot. The velocity of a wheel will be mapped to the values of the sensor at the same side of the robot in an excitatory manner. The robot tends to steer away faster from a shoal mate when there is a higher chance of collision and slow down when reaching a safe separation distance. The weight of this behavior is modulated by the collaboration need (the closer the shoal mates, the lower the collaboration need, the higher the weight), and finally we applied a global discount to the whole group of schooling behaviors.

# apply the appropriate sensorimotor connection

left_activation = left

right_activation = right

# calculate the weight

weight = min(1., max((1 - robot.collaboration_need - robot.collaboration_discount), 0.))

return left_activation, right_activation, weight

The cohesion behavior: causes the animal to move in a direction that moves it closer to the centroid of the nearby shoal mates. In Reynolds' work, if the group is maintained stable, the distance to shoal mates is approximately the same in all directions. In this case, the shoal centering urge is small. If a mackerel is on the boundary of the shoal, its neighbors are on one side. The centroid of the local shoal mates is displaced from the center of the neighbors toward the body of the shoal. Here the centering urge is stronger. In our case, we developed this behavior partially based on the basic love Braitenbergs behavior. The distances to shoal mates are proximity values detected by the two proximity sensors of the robot. The velocity of a wheel will be mapped to the values of the sensor at the same side of the robot in an inhibitory manner. The robot will try to approach the shoal mates faster if it's too far away from them and slows down when it gets closer. The weight of this behavior is also modulated by the collaboration need (the closer the shoal mates, the lower the collaboration need, the lower the weight), and finally we applied a global discount to the whole group of schooling behaviors.

# apply the appropriate sensorimotor connection

left_activation = 1 - left

right_activation = 1 - right

# calculate the weight

weight = min(1., max((robot.collaboration_need - robot.collaboration_discount), 0.))

return left_activation, right_activation, weight

The alignment behavior: complements the cohesion rule regarding the centering movement towards the centroid of local shoal mates as well as to make sure all the members will have the tendency to navigate in the average heading of the shoal. In previous works, this rule is usually calculated based on the global orientation and position of the group as some sort of vectors. This requires the agent's understanding of the global state of the scene, which goes beyond the scope of local sensing and reactive behaviors. In our case, we came up with a solution of calculating the moving direction of a neighbor by comparing the immediate proximity value and the previous proximity value. The mackerel who goes in the opposite direction with the other two mates will be the one who needs to change its direction and follow the majority. We also allowed this rule to have the highest weight among the schooling behaviors, and finally, we applied the global schooling discount. We observe that this behavior indeed helps the member steering towards the center point of the local mates and moving towards the average heading of them. But it cannot ensure that all the members will move in the same direction all the time (sometimes they will).

# save the previous readings

prev_left = left

prev_right = right

# calculate the weight based on the comparision of readings

weight = 0

if prev_left < left and prev_right < right: # both other shoal mates are approaching the robot

# switch on the behavior

weight = 1 - robot.collaboration_discount # always has highest weight among schooling behaviors when being switched on

# rotate to change direction if both other shoal mates are going in the opposite direction

left_activation = 0

right_activation = 1

return left_activation, right_activation, weight

We also notice that an epuck only has 2 sensors in front of it, which may cause it unable to detect mates out of the local sight. Other mates will tend to ignore the lost one. The lost animal needs to look for the group by rotating itself until the schoal mates are within sight.

# calculate the weight based on the distance of shoal mates

weight = 0

if left == 0 or right == 0: # losing sight of one of the shoal mates

# switch on the behavior

weight = 1 - robot.collaboration_discount # always has highest weight among schooling behaviors when being switched on

# rotate until the shoal mates are within sight

left_activation = 0

right_activation = 1

return left_activation, right_activation, weight

The combination of those behaviors keeps the agents together, eventually forming a triangular group. The emergent triangular formation is an interesting outcome of our solution since it expands and contracts as the cohesion and separation change in strength.

Environmental dynamics

The obstacle avoidance behavior: real flocks and schools sometimes split apart to go around an obstacle. We developed this behavior based on the basic shy Braitenbergs behavior. The distances to objects (corals, walls, pillars, etc. ) are proximity values detected by the two proximity sensors of the robot. A wheel will be cross-wired to the sensor at the opposite side of the robot in an inhibitory manner.

The foraging behavior: depends on the animal's hunger (energy level). The weight of this behavior is modulated by the energy level (the lower the energy level, the higher the foraging need, the higher the weight). When the animal is full, it tends to ignore and steer away from spheres. The weight of this behavior is also modulated by the energy level (the lower the energy level, the higher the foraging need, the lower the weight).

In the beginning, the mackerels try to catch detected food but still spend efforts in staying within group. They become more aggressive towards food over time and split apart to forage. They even compete for spheres.

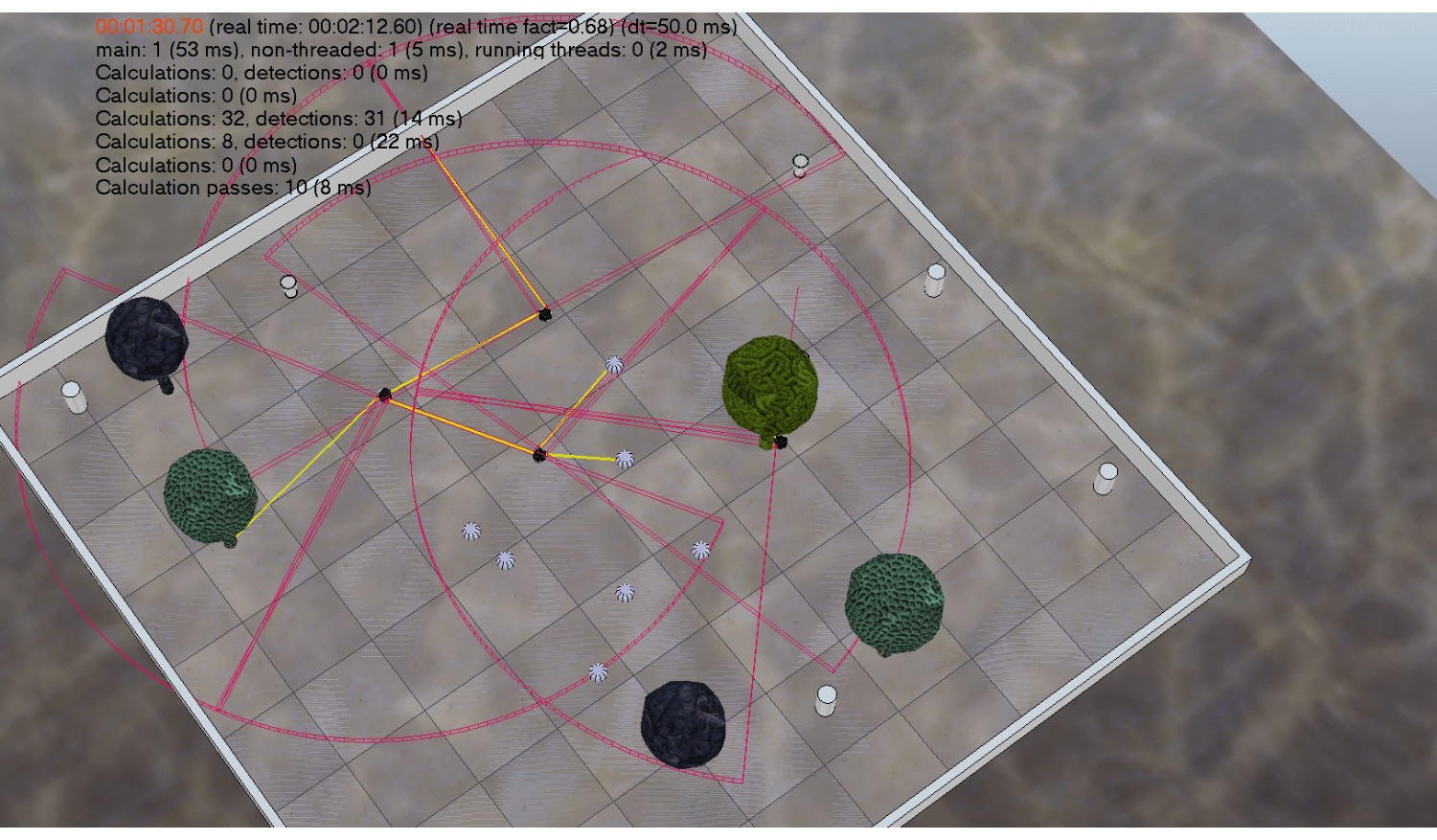

The anti-predation behavior: based on the basic fear Braitenbergs behavior. The weight of this behavior is modulated by the security need (the closer the predator, the higher the security need, the higher the weight), and finally, we applied a global anti-predation discount. The mackerels will flee while trying to stay within-group or split apart and then reunite based on whether which need is more intense at the moment: security or collaboration.

Each mackerel try to steer away from the predator for its own sake and eventually split apart. They perform grouping again when the predator is out of sight.

In nature, the predator also regulates its hunting behavior by the number of prey in a group: it will target the lonely fish rather than a collaborative school. We would like to imperfectly demonstrate this principle in our project, with the weight of hunting behavior calculated base on the energy level as well as the risk the predator has to tolerate while hunting multiple preys. Another interesting observation is that when two preys have equivalent distances to the predator, the predator will move forward in between them, very much reflecting the anti-predation benefit of schooling. However, there is a limitation here. The epuck can only detect a maximum number of two objects, and it also cannot tell whether the two proximity sensors are sensing the same mackerel or not. Thus, in the case of a perpendicular attack (both sensors detecting the same mackerel), the predator will apply a risk when it shouldn't.

Data analysis

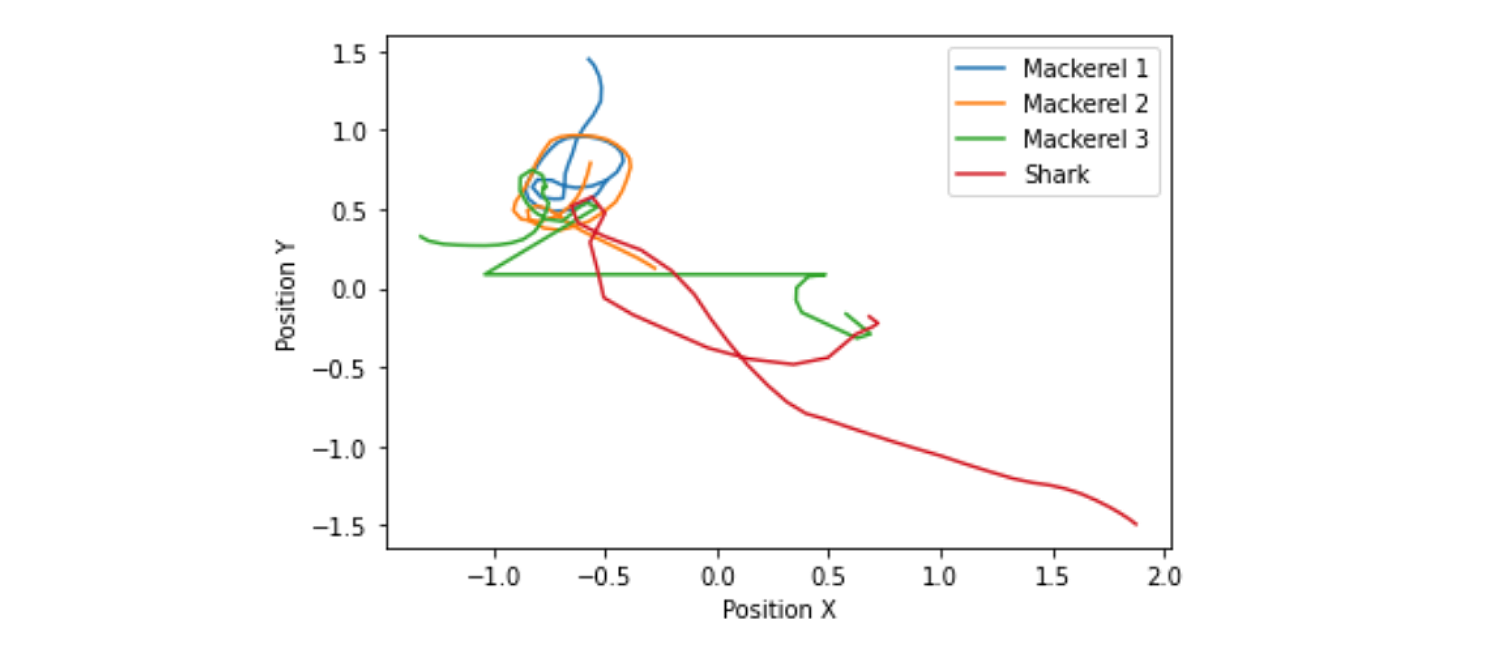

Movements of all robots during the simulation

We plotted the position (X,Y) of the robots to keep track of their movements during the simulation. As can be observed from the plot, the red color represents the predator (shark) and the others are preys (mackerels). Following the schooling behaviors, preys gather together in the beginning while there is no threat caused by the predator. Later, when the shark approaches, the need for security increases and the preys start to avoid the shark, thus, leading to a split amongst them. In this simulation, the mackerel 3 is separated from the shoal mates and in the end is attacked by the shark.

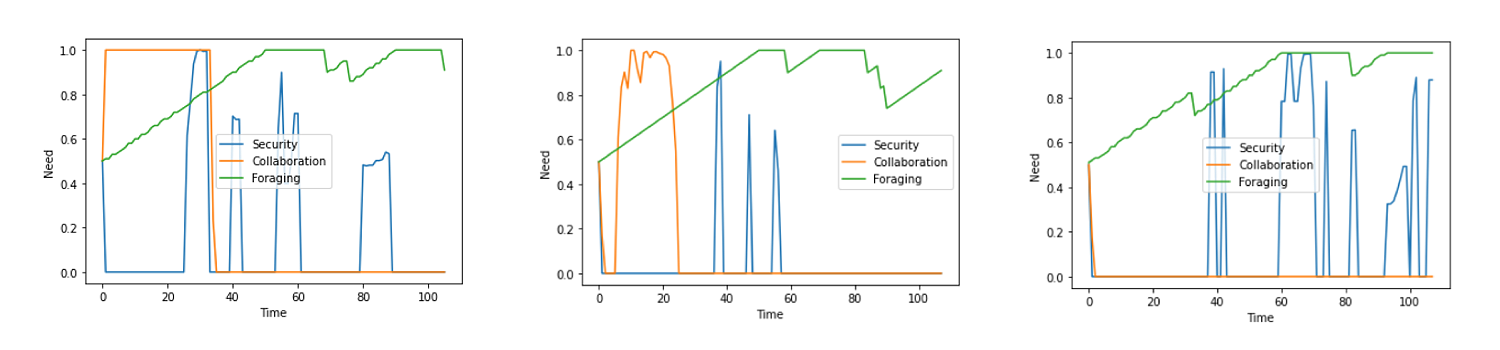

Intensities of multiple needs against time

As explained above, in this project we prioritize schooling over foraging and anti-predation over schooling. We did some plots that are representative of the trade-offs between multiple needs for each of the three mackerels. The plots explain the changing priority with respect to the internal drives of the agents and increment in time. Therefore, in the beginning, the need to stay together (schooling behaviors) is seen. Over time, consuming food to gain energy becomes prior. The nature of security is fluctuating because it is dependent on the predator’s behavior.

Future development

Low polarity: The Reynolds rules were not precisely replicated in our project. The mackerels didn't perform perfect schooling movements of constantly heading towards the same direction. Given the constraints of local sensing and reactive behaviors, we should research further to come up with a better alignment rule, probably with a refuge/target destination or a leader.

Migration: We can make the school going towards a refuge or a target destination with richer food resources.

Lack of prey identity: The predator can only detect a maximum number of two objects, and it also cannot tell whether the two proximity sensors are sensing the same individual prey or not. We can further research to come up with a future solution that allows the predator to identify moving objects, store their locations, and calculate the density of the school.

Mix-species shooling: Taking advantage of various sensorimotor abilities of multiple species, as well as demonstrating the different ranking systems of different species. In this case, the flock does not consist of the same species but of several species that gain a benefit from each other.

Cognitive interactions: If we want the agents to fulfill several needs at the group level, we might need a more efficient simulation setup and a model that can account for how low-level dynamic processes (i.e what we observed here) interact with high-level strategic processes (e.g. memory and learning, prediction of environmental perturbations and adaption, goals and planning, send and handle notifications to get information from shoal mates, etc.).